WORRIED NURSING CLINICALS WILL BE BANNED? PARTNER UP

THE BEST WAY TO ENSURE NURSING CLINICALS CONTINUE IN A PANDEMIC:

SET UP AN ACADEMIC-PRACTICE PARTNERSHIP

Last spring, when the novel coronavirus began spreading across the United States, students expressed a lot of fear. Fear of getting sick. Fear of loved ones becoming ill. Fear of not graduating due to missed clinicals.

Their fears were — and continue to be —valid.

Now, however, students are overcoming their fears as nursing groups join with providers to get students back into clinical settings. It's all happening due to the development of academic-practice partnerships.

FEELING GOOD ABOUT GETTING BACK ON THE FLOOR

.png?sfvrsn=33b805e9_0&MaxWidth=400&MaxHeight=&ScaleUp=false&Quality=High&Method=ResizeFitToAreaArguments&Signature=4BFED9037B558C41D32A3E7B8467B99A7F90FC90)

Carly Schlabaugh (Williamsburg, Iowa), a recent graduate of the University of Iowa (UI) College of Nursing (Iowa City), was thrilled about being getting back on the clinical floor last spring. Afterward, she posted a grateful, public message on Facebook:

“In the wake of today’s current events, I have never been more proud to become a nurse. What an honor it has been to stand alongside some of the bravest and most resilient healthcare workers on the front lines during this time. I have found my passion in nursing and know that I was meant to care for others, especially during times where everyone else is running in the other direction. With that said, I’m so excited to share that I have accepted a position at the University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics (UIHC) in the Cardiovascular Intensive Care Unit (CVICU).”

The irony of where she ended up being hired was not lost on Schlabaugh. At the end of her post, she added, with some wry humor, “It’s safe to say that I’ve come a long way from passing out from seeing a deer heart during my high school anatomy class to becoming a cardiac nurse.”

Similarly, fellow BSN student Alexa Atkins (Morton, Ill.), described her experience to a local TV news station. Atkins said she’d seen patients with much more fear and anxiety during the pandemic than patients normally express when they are in the hospital. Being able to comfort them made her preceptorship especially meaningful.

Similarly, fellow BSN student Alexa Atkins (Morton, Ill.), described her experience to a local TV news station. Atkins said she’d seen patients with much more fear and anxiety during the pandemic than patients normally express when they are in the hospital. Being able to comfort them made her preceptorship especially meaningful.

“We [were] an extra person to hold their hand and help them in this fearful time,” she explained. Working in stressful situations like the COVID-19 pandemic also boosted her confidence and courage, she added. The experience had not only prepared her educationally, she said, but it had given her the skills and confidence to feel like she was playing a pivotal role.

“You kind of forget about the fear that you yourself have,” she said, “and when you get home, maybe that fear comes back. But when you’re there, there’s just something special.”

Anita Nicholson, PhD, RN, Professor (Clinical), UI Associate Dean for Undergraduate Programs, underscored the importance of students’ experience when she spoke with the TV reporter.

Schlabaugh, Atkins, and a slew of other students can thank a group of dedicated nursing leaders for the opportunity to finish their nursing studies. Instead of venting about their frustration when clinical doors slammed shut, these individuals got to work.

CONVINCING PRACTICE PROVIDERS TO RECONSIDER

While not a new concept, academic-practice partnerships gained the spotlight last March as the pandemic began spreading throughout the world. A group of 10 of the nursing profession’s leading organizations issued a policy brief recommending an increase in academic-practice partnerships between healthcare facilities and prelicensure nursing programs during the COVID-19 crisis. The purpose was to address both the growing burdens on nurses and the lack of available clinical sites for current RN students.

DOWNLOAD THE ACADEMIC-PRACTICE PARTNERSHIP POLICY BRIEF

The policy brief was stark in its realism. “After observing the pattern of the virus, the U.S. anticipates an overabundance of patients inundating hospitals and possibly overwhelming the entire U.S. healthcare system.

“A significant demand is being placed on the entire nursing workforce, and this is anticipated to increase at an alarming rate,” the brief said.

Despite that demand, many hospitals and healthcare facilities put a halt to clinical experiences for nursing students. They feared putting students at risk or having them carry the virus home to others. Plus, the providers faced a critical shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE); they had none to spare for student nurses.

The situation created a vicious circle. Without nursing clinical experience, students’ ability to graduate was at risk. If they couldn’t graduate, even fewer nurses would be available for a workforce desperately in need and facing overwhelming exhaustion.

For a bit, concerns lessened slightly when the pandemic seemed to be leveling off. Recently, however, it has surged back to frightening levels with fears it may worsen during winter months. As a result, your concerns about students’ continued lack of access to clinicals may be surging too.

The time is imperative, then, to learn how other nursing programs — who set up academic partnerships last spring — got the process started.

STEPS FOR IMPLEMENTING ACADEMIC-PRACTICE PARTNERSHIPS FOR YOUR STUDENTS’ CLINICALS

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) released a video in mid-June in which participants explained the success of their academic-practice partnerships. (NCSBN also has a list of helpful FAQs on its website.)

|

LAYING OUT THE SPECIFICS OF YOUR ACADEMIC-PRACTICE PARTNERSHIPS

The guidelines kick off with detailed aspects of what a partnership should encompass with links to other helpful resources: • Academic-Practice Partnership Implementation Tool Kit • Outcomes Matrix • Webinars • Exemplary Academic-Practice Partnership Award Winners and Exemplars • Academic-Practice Partnership Community |

Maryann Alexander, PhD, RN, FAAN, Chief Officer, Nursing Regulation, NCSBN, explained the process.

“Under this model, students are hired by the hospital and considered paid employees, while — at the same time — they earn clinical credit through their educational institution with faculty to oversee and evaluate their skills,” she said.

Several individuals shared their experiences in how they made the model work.

.png?sfvrsn=7b705e9_0&MaxWidth=150&MaxHeight=&ScaleUp=false&Quality=High&Method=ResizeFitToAreaArguments&Signature=E349A2FB080AF88E487B58A8A05E24AEFD7DD078) The foundation of success, said Julie Zerwic, PhD, FAHA, FAAN, Kelting Dean and Professor, UI College of Nursing, was collaboration.

The foundation of success, said Julie Zerwic, PhD, FAHA, FAAN, Kelting Dean and Professor, UI College of Nursing, was collaboration.

“We came together with our academic medical center, the UIHC, and Kirkwood Community College (Cedar Rapids, Iowa) … to identify what opportunities we had to continue clinical placements,” she said. “We quickly decided that the priority should be with the students who were graduating in May. The University of Iowa Hospital committed to making sure that students who were placed there would actually complete their internship hours.”

To kick-start the situation, Dr. Zerwic told ATI that her program implemented processes to onboard graduates more quickly than normal. For example, it worked with its registrar’s office to find mechanisms to speed the issuing of final transcripts.

“We ended up finishing the final semester coursework a few days early, which gave the registrar the opportunity to run the transcripts before they got caught up with the rest of the university finishing,” she explained. “This eliminated 2-3 weeks of time.”

Other important work took place in coordinating with the Iowa Board of Nursing to implement an emergency licensing process. Once the BON identified those requirements, the UI nurse educators passed the information along to students. Students then could get the necessary materials to the board as quickly as possible.

Communicating the information to its main practice partner, UIHC, was crucial as well, Dr. Zerwic said. “They were aware of the emergency license and what new graduates could and could not do,” Dr. Zerwic added. “They got their new graduates into their positions quickly and started orientation much earlier than they typically would for May graduates.”

Communicating the information to its main practice partner, UIHC, was crucial as well, Dr. Zerwic said. “They were aware of the emergency license and what new graduates could and could not do,” Dr. Zerwic added. “They got their new graduates into their positions quickly and started orientation much earlier than they typically would for May graduates.”

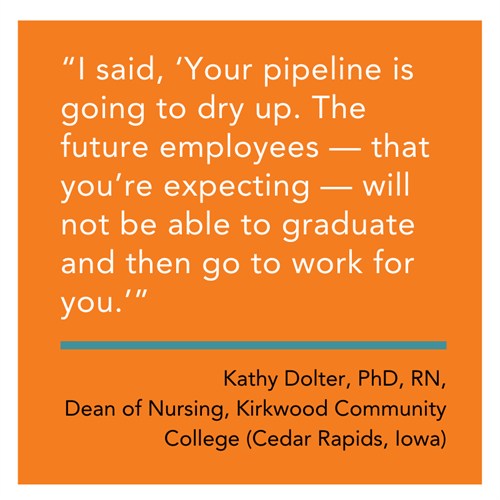

Kathy Dolter, PhD, RN, the Dean of Nursing at Kirkwood Community College, worked closely with Dr. Zerwic. Even before the pandemic, Dr. Dolter’s program already had partnerships in place with several large institutions, such as Iowa City Mercy Hospital and Mercy Cedar Rapids, as well as smaller, critical-care access hospitals.

As Dr. Zerwic noted in the NCSBN video, the UIHC got the message. It immediately agreed to allow students who were already working as patient-care techs to begin preceptorships on the units where they already expected to work after graduation. (A major benefit to this plan, Dr. Dolter noted, was that it cut down on orientation and residency time.)

As Dr. Zerwic noted in the NCSBN video, the UIHC got the message. It immediately agreed to allow students who were already working as patient-care techs to begin preceptorships on the units where they already expected to work after graduation. (A major benefit to this plan, Dr. Dolter noted, was that it cut down on orientation and residency time.)But getting those students placed fulfilled only a fraction of the UIHC’s future employment needs, not to mention other providers in the state. So, Dr. Dolter began proactively encouraging Kirkwood students to apply to whatever their provider of choice was, even if that facility wasn’t — yet — allowing nursing clinicals like UIHC.

She explained to students that those hospitals might allow them to finish preceptorships if the institutions knew the students were committed to them.

With that effort in motion, Dr. Dolter then contacted nonparticipating providers to explain the partnership model that the UIHC, UI College of Nursing, and Kirkwood had implemented She, with other area nursing programs such as Mount Mercy University (Cedar Rapids, Iowa), asked them to consider establishing such a partnership model. She identified that Kirkwood had urged students to apply for jobs at their hospitals. She noted that the UIHC was already prehiring Kirkwood students and then allowing those who were prehired to complete their preceptorships. With a partnership such as that between the UIHC, UI College of Nursing, and Kirkwood, she highlighted that the UIHC now had a ready stream of future employees to meet their nursing “pipeline” needs.

Dr. Dolter’s tactics worked. Once providers understood the consequences of closing clinicals and had addressed PPE and internal process constraints, they agreed to participate and began letting students back in.

EDUCATING STUDENTS ABOUT THE PARTNERSHIPS

While many students were concerned about getting sick from the virus, Dr. Dolter said others were “terrified” of not progressing. To allay those fears, Kirkwood began weekly virtual meetings with students to explain the academic-partnership plan. “I was able to answer direct questions from the students and help cultivate ambassadors for the program due to the information sharing that occurred,” Dr. Dolter said.

Iowa wasn’t the only state seeing success with pursuing the partnerships. Idaho nursing leaders also jumped on board. Sarah Phipps, MSHSA, BSN, RN, Associate Executive Director of the State of Idaho Board of Nursing, took similar proactive steps to Dr. Dolter’s. Phipps met remotely with student nurse leaders at each Idaho nursing program.

Iowa wasn’t the only state seeing success with pursuing the partnerships. Idaho nursing leaders also jumped on board. Sarah Phipps, MSHSA, BSN, RN, Associate Executive Director of the State of Idaho Board of Nursing, took similar proactive steps to Dr. Dolter’s. Phipps met remotely with student nurse leaders at each Idaho nursing program.

Based on the number of applicants, she believed students were excited about the opportunity. As of mid-July, she said, “We received 394 nurse apprentice applications and have issued 352 Nurse Apprentice Authorizations. We received 458 New Graduate Temporary Licenses applications and have issued 385 New Graduate Temporary Licenses. For a state that has 10 colleges/universities,” she added, “I was very impressed with the quantity of applications we received.”

In talking with students after their preceptorships had ended, she said they seemed just as excited.

“The students have had an amazing experience collaborating with licensed nurses in this unique structure,” she noted. “It really is a model that strengthens the entire nursing community, from education through practice.”

SPREAD THE WORD TO REIMPLEMENT NURSING CLINICALS IN YOUR STATE

With the success of those in Iowa and Idaho, you needn’t start from scratch in setting up academic-practice partnerships in your state.

Once the UI College of Nursing and Kirkwood had worked out an agreement with UIHC, they developed a joint statement to encourage other providers to open their doors. In early April, they sent their statement to the Iowa Organization of Nursing Leadership, the Iowa Association of Colleges of Nursing, and the Iowa Community College Nurse Educator Directors’ Association.

In the letter, the partners mentioned the public policy created by the nursing profession’s leading organizations: American Nurses Association (ANA), National League for Nursing (NLN), NCSBN, the American Organization for Nursing Leadership (AONL), the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), Organization for Associate Degree Nursing (OADN), Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing (ACEN), and the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education (CCNE).

The letter then described the plan worked out with UIHC and advocated that other practice partners could follow similarly. Specifically, the letter asked practices to:

- Allow students currently employed to complete their preceptorships or clinical hours

- Allow students who they planned to hire upon graduation to complete their preceptorships or clinical hours on the unit or area for which they would be hired.

Following the policy developed by NCSBN, et al., the letter also suggested that providers implement paid preceptorships that would allow students to be designated as employees. The letter further encouraged providers to develop joint-appointment models of nursing clinical instruction, where the instructors of clinical groups were also nurses employed by the organization on that clinical area.

In June, the 3 original partners were joined by the IONL in sending a follow-up letter (see at right) to the original recipients. In late July, as a direct result of the letter, members of the Iowa Board of Nursing staff convened a panel of nursing academic and practice leadership organizations to discuss how to ensure the “pipeline” of nursing students continues to meet Iowa workforce needs.

In June, the 3 original partners were joined by the IONL in sending a follow-up letter (see at right) to the original recipients. In late July, as a direct result of the letter, members of the Iowa Board of Nursing staff convened a panel of nursing academic and practice leadership organizations to discuss how to ensure the “pipeline” of nursing students continues to meet Iowa workforce needs.

OADN has taken this idea to a national level after organizing the OADN COVID-19 National Task Force in early June. The task force is a diverse group of OADN members and stakeholders — including Dr. Dolter — from across the country in regions urban and rural, said OADN CEO Donna Meyer, MSN, RN, ANEF, FAADN, FAAN. Meyer and Director of Strategic Initiatives Mary Dickow, MPA, FAAN, coordinated the group’s activities.

OADN has taken this idea to a national level after organizing the OADN COVID-19 National Task Force in early June. The task force is a diverse group of OADN members and stakeholders — including Dr. Dolter — from across the country in regions urban and rural, said OADN CEO Donna Meyer, MSN, RN, ANEF, FAADN, FAAN. Meyer and Director of Strategic Initiatives Mary Dickow, MPA, FAAN, coordinated the group’s activities.

“The task force’s purpose was to provide a national perspective and guided consideration,” Meyer said, “and generate ideas to address future teaching/learning structures and opportunities in nursing education.”

She added that the task force also aimed to “create a repository of information for dissemination of the identified tasks,” of which the letter was a result. The task force identified innovative methods of restructuring the teaching/learning process; recognized the need for modifications based on the pandemic; developed strategies for providing meaningful clinical learning opportunities; discussed academic/practice partnership considerations; and created a plan for collaborating with industry partners for high quality and safe return of students to clinicals.

Educators can take advantage of both OADN’s letter (see the link below to download a Word version that you can customize) and the communications created by the Iowa group to develop their own partnerships. (See the letter above right with a link to download a PDF.)

Dr. Dolter said she knows such solutions aren’t perfect. “Some people may say, ‘I’m philosophically opposed to just putting people where they’re going to work,’” she admitted. After all, educators want students to gain multiple types of experience and to expose them to as many employers as possible, and she agreed that was best for students.

In the current situation, however, she said you’ve got to be pragmatic.

“It's much better than not going to clinical,” she added. “No clinical at all, to me, is not an option.”

DOWNLOAD THE OADN LETTER IN A FORMAT YOU CAN CUSTOMIZE

| ATI is working with programs just like yours to help them through the current challenges. From tips for moving your classroom online to best practices for using ATI online learning, testing, virtual simulation, and clinical hour replacement solutions, we’ve got answers. Stay up to date on future webinars, as well as those available in the archive of ATI Academy. Contact us to get more details on how ATI can help. |