Finding courage in facing the crisis of nurse mental health

Why we can’t fail in educating ourselves and our students about nurse mental health

“I don’t want to be a nurse anymore … I’m not sure how much longer I can do this.”

It was 3 a.m. and one of those eerily quiet moments seldom experienced by bedside nurses. But that particular early morning hour, those working found themselves able to take a short breather — a rare opportunity to simply rest and talk.

The conversation soon turned to an incident that was becoming disturbingly common: the suicide of a local nurse while he was on duty. And, quietly, the nurses on duty began sharing how they could understand such despair.

One after the other commented on their doubts about continuing to work in the career they loved.

Remembering back, Joshua Paredes, RN-BC, a nurse at the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center, still sounded a bit in awe of the experience.

“I couldn't believe that talk was happening. I couldn't believe how honest we were being with each other, because that's not even — that is not the normal culture in nursing at all,” he recalled.

If you or someone you know may be considering suicide, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741.

(En Español: 1-888-628-9454. Deaf and hard of hearing: 1-800-799-4889)

NURSE MENTAL HEALTH: THE ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM

The passion — and compassion — of nurses fuel their skills in caring for others. But those qualities also put them at higher risk for suicide, burnout, and other mental health issues. And facing strict time limits with clients, additional duties such as cleaning rooms, and longer hours due to short staffing, the pandemic added even greater emotional challenges:

- Isolation — spending hours in a single intubated client’s room as the primary caregiver to reduce the number of people exposed to the COVID-19 virus

- Fear — of contracting the virus or carrying it home to their loved ones

- Grief — from experiencing an overwhelming amount of death, especially in being the only person to hold clients’ hands during their last moments.

Nurses were already at higher risk for suicide than the general public before the pandemic. The American Nurses Association says, “The profession of nursing is fertile soil for risk factors of suicide.” The organization lists a phalanx of stressors, such as:

- Exposure to repeated trauma

- Scheduling long, consecutive shifts

- Repeated requests for overtime

- Workplace violence, incivility, and bullying

- Inadequate self-care

- Financial stressors

- Access to and knowledge of lethal substances

- Constant, high workplace stress

- Feeling unsupported in the role

- Fear of harming a patient

- Depression and undertreatment of depression

- Smoking

- Substance abuse.

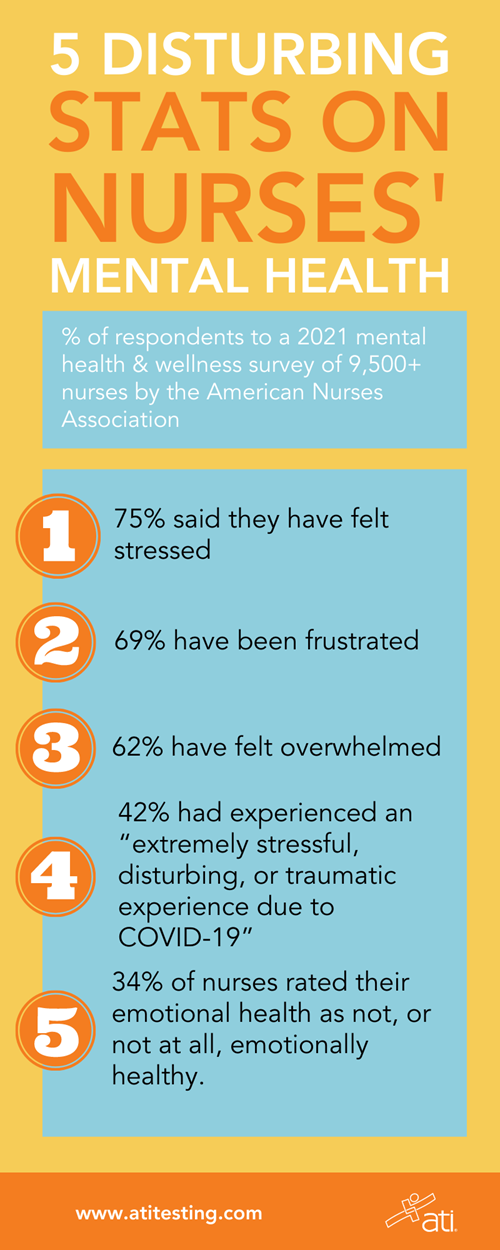

In a 2021 mental health and wellness survey of more than 9,500 nurses, the ANA detailed multiple disturbing statistics.

Specifically:

- 75% said they have felt stressed

- 69% have been frustrated

- 62% have been overwhelmed

- 42% had experienced an “extremely stressful, disturbing, or traumatic experience due to COVID-19”

- 34% of nurses rated their emotional health as not, or not at all, emotionally healthy.

At special risk are the youngest nurses. The ANA’s study reported, “Among those under 35, data reveals elevated stress, depression, and anxiety; increased suicidal thoughts; increased reports of trauma; lower emotional health and resiliency scores; and higher intent to leave.”

For nurse educators, these facts point to a greater need to mentally prepare students for the challenges of their chosen careers.

[Read more on how to aid students and peers at risk.]

THE IMPACT OF BURNOUT ON NURSES’ MENTAL HEALTH

News of burnout in nurses has become common. But many don’t recognize that burnout doesn’t simply leave individuals fatigued.

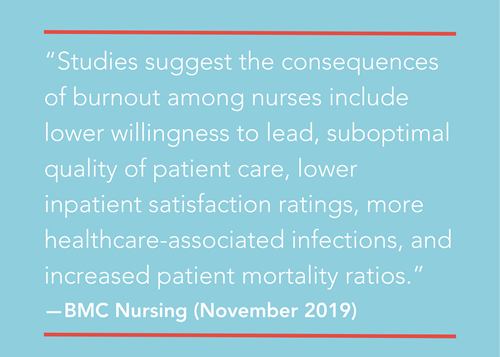

“Studies suggest the consequences of burnout among nurses include lower willingness to lead, suboptimal quality of patient care, lower inpatient satisfaction ratings, more healthcare-associated infections, and increased patient mortality ratios,” reports a 2019 cross-sectional study on nurses and job performance in the November 2019 issue of BMC Nursing.

Such client concerns should be enough to pique the attention of hospital CEOs in addressing the issue. After all, such detrimental consequences impact the bottom line, and — according to an annual survey conducted by the American College of Healthcare Executives (ACHE) in which they ask hospital CEOs about their top issues — financial concerns have consistently led the list of their biggest challenges. Today, however, burnout appears to finally have appeared on their radar. That’s because, for the first time since 2004, personnel challenges are cited as the No. 1 issue.

Paredes, whose friend was the nurse who took his life, believes administrators are definitely noticing.

“Nobody really wanted to talk about [mental health] before,” he said. “And I think now that employers are starting to feel the crunch — the staffing crisis — they're starting to panic. And that's why this is kind of getting discussed.”

He understands it won’t be easy for institutions to implement the necessary changes.

“I get it,” he explained. “It's hard for you to look at a problem and feel like maybe you possibly [could] be complicit in it.”

So, while he thinks change will happen, he’s not waiting for institutions to initiate it. He’s taking action himself.

First, he took a serious look at his own life. “I recognized I had some signs of burnout, and that was frightening to me,” he explained. So, he switched his job from full-time to part-time.

Next, Paredes began taking steps to help other nurses in crisis. He started an organization “to advocate for nurses living with mental illness and provide a digital crisis intervention platform to members of the nursing community who are considering suicide.”

“We've got to make this career sustainable for those of us who chose to enter it,” he added.

THE STIGMA OF DISCUSSING MENTAL HEALTH

As Paredes has suggested, despite the recent publicity of nurse burnout, mental health, and suicide, nurses don’t tend to talk about these issues. In fact, the stigma of mental illness is entrenched in society as a whole.

As Paredes has suggested, despite the recent publicity of nurse burnout, mental health, and suicide, nurses don’t tend to talk about these issues. In fact, the stigma of mental illness is entrenched in society as a whole.

“But it's obviously a much more important issue in healthcare and trying to get people in healthcare to recognize that they can reach out for help,” he said.

That stigma sets up a dangerous situation for nurses. In an article on the topic, Medpage Today (Oct. 22, 2021, issue) Washington Correspondent Shannon Firth wrote, “Nurses experiencing burnout were twice as likely to have thoughts of suicide, and those with symptoms of depression were 11 times as likely to experience suicidal thoughts, a survey study found.”

Firth’s article went on to quote an author of that survey, Elizabeth Kelsey, DNP, APRN, CNP, of the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minn.). Dr. Kelsey told Firth, “I think there’s still stigma around mental health and people seeking help, difficulty getting [time off] work, and even worries about confidentiality,” adding that some state nursing boards require disclosure of mental health problems.

Paredes had similar concerns. He admitted to being fearful about his employer learning that he was seeking therapy. But nurses must get past this hesitation. They need to remember that they are worth protecting.

“We have to be No. 1. Don’t clock out on the most important patient,” he noted, referencing the words he used in naming his organization. “It’s so important. Don’t forget about ourselves."

IN RECOGNITION OF MAY AS MENTAL HEALTH AWARENESS MONTH, ATI IS PUBLISHING A SERIES OF ARTICLES AIMED AT NURSES' MENTAL HEALTH. READ MORE AT:

Read about raising awareness, screening proactively, and delivering evidence-based care on the blog by our sister company, APEA. And for continuing education opportunities focused on suicide, visit our sister company, Nursing CE.

What concerns do you have about nurses' mental health? Share in the comments below.