HOW TO REPLACE A CLINICAL DAY IN THE VIRTUAL CLASSROOM: USING REAL LIFE

| Real Life scenarios were developed by nurse educators to provide experience with the variety of situations nurses face in real life, without the need for live clinical presence or risk to client safety. Students develop an emotional connection to each situation and each live-actor client, who look and sound like they’re truly in pain, confused, or angry. These realistic clinical scenarios give students experience building the clinical reasoning, patient safety, and clinical decision-making skills they need. |

Janet Kane, MSN, RN, CNE, ATI Nurse Educator Integration Specialist (now retired), described the multifocused process that Real Life Clinical Reasoning delivered.

“Students prepare on their own by working through a predeveloped lesson plan that addresses many components,” she explained. The lessons apply to a variety of subject areas: RN and PN medical-surgical, RN maternal newborn, RN mental health, and RN nursing care of children. Within those subject areas, topics cover more than 2 dozen specialties, from pneumonia to bipolar disorder.

Depending on what your state board of nursing allows, use of a scenario could count for anywhere from 6 to 8 hours of clinical time, Kane said. Even if you don’t — or can’t — count it toward clinical hours, Kane added, “It’s still a great opportunity for students to process the information in the scenario and relate it to what they would do in a clinical environment.”

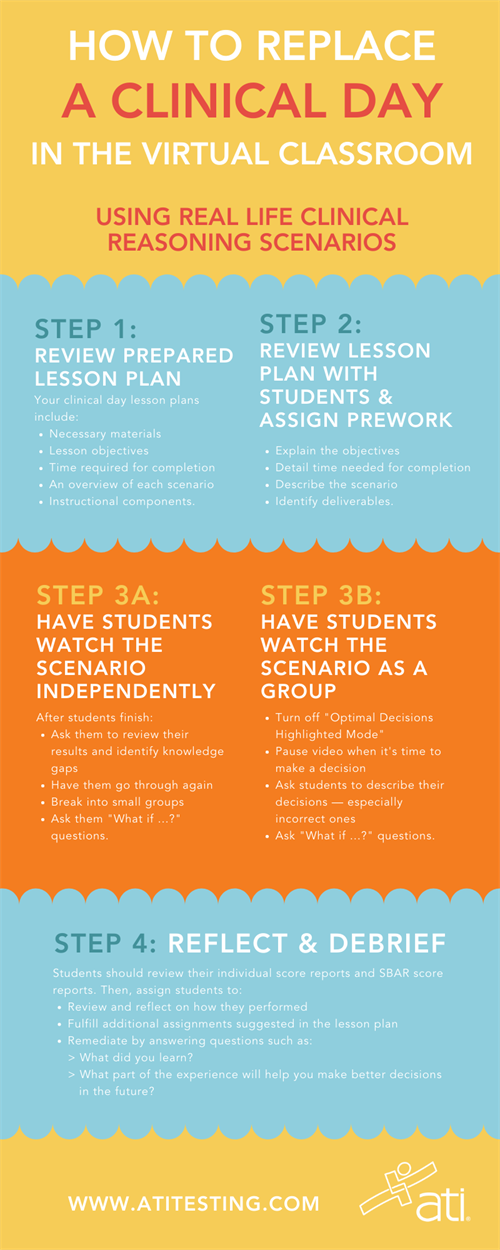

Here, Kane provided some tips for putting Real Life Clinical Reasoning scenarios to work for a clinical-replacement day.

DOWNLOAD THE INFOGRAPHIC AS A HANDY REFERENCE

Step 1: Review the prepared lesson plan.

You’ll find clinical day lesson plans for each topic area in ATI’s Real Life Clinical Reasoning Scenarios in the “Resources” section after you log in to the ATI website. (Click on the “Products & Integration” card, and then scroll to “Real Life.”). Also look for the new overview document, “Virtual Clinical Replacement Lesson Plan,” which was recently added to support educators dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The lesson plans have specific information indicating what materials are needed, what the objectives of the lessons are, the amount of time likely to complete, an overview of the scenario, and specific instructional components. They also include deliverables that are developed throughout the lesson activities,” Kane explained.

Step 2: Review the lesson plan with students & assign prework.

Explain the objectives of the lesson and how much time students can expect it to take (including prework). During this explanation, describe the scenario in general. Then identify the individual tasks (deliverables) students will need to complete as prework before coming together in the virtual classroom. For example, instruct students to download and print out the specific active learning templates related to the specific scenario, such as Medications, Nursing Skill, and System Disorder.

“We want them to come to the scenario as prepared as possible, so that the experience and the decisions they’re making are based on the application of content, as opposed to a general reaction with less information,” Kane explained.

When they have finished their hand-written, prework deliverables, have them take a pic, and submit the documents to you as evidence of their work.

Step 3a: Have students watch the scenario independently.

While watching the scenarios, students will make decisions that help them develop their critical thinking, and clinical judgment and reasoning skills, while striving for optimum performance. As they watch, they will have options in terms of which response to choose.

“Depending on how they respond,” Kane said, “determines which next screen they’re going to see. With these scenarios, we’re always trying to be sure that students walk away with a learning experience if they didn’t choose the optimal answer,” she added. “We’re going to give them an opportunity to see that their choice wasn’t, perhaps, the optimal response, and then we’ll continue to move through the scenario.”

This process allows student to continue working through the scenario from a best-decision perspective, Kane explained. After all, an important part of the clinical learning experience in both the onsite and virtual environment is role development, learning from less-than-optimal decisions, and applying that knowledge to future experiences.

“Having the students go in and work through the scenario, review, understand where their gaps were, and then go back in and try to perform more effectively is a way of reinforcing that positive learning,” Kane said.

You’ll still need to be actively engaged in the virtual learning experience when students watch the scenarios for independent completion. For example, within small groups, Kane suggested thinking beyond simply what was in the scenario and use it in a variety of additional ways. Ask questions such as “What if?” or “What would the priority be?” or “How would your decisions change if …?”

“These queries will drive students toward application of what they know, as opposed to regurgitation,” she said. “It’s an opportunity for them to show that they can apply the information they understood.”

Step 3b: Watch the scenario as a group.

Make sure the “Optimal Decisions Highlighted Mode” is turned off, so students don’t immediately see the correct answers. (The mode is preset to the “off” position.) Doing so, Kane explained, means students will have to respond to what they see just as they would in a clinical environment.

As you lead the viewing and discussion, you can pause the video when it’s time to make decisions.

“Have the students dialogue on the choices they make, specifically why they chose an answer that turns out to be incorrect,” Kane said. “Even though they’ve been through the scenario before, even though they’ve seen it before, collaborating to understand what the best answer is — and having faculty facilitate any muddy points that may remain as a result of having gone through — is beneficial.”

Reviewing as a group also allows you to ask “What if?” questions. Kane suggested prompting students on:

- What if I changed this aspect to this particular scene?

- How would your decision change if …?

- What is your priority if …?

- What would change if the patient was positive for COVID-19?

- What if I applied this cultural consideration to this scene?

- What if the discharge planning required alteration? For example, the family was going to be taking this patient home, but it turns out they’re not available after all.

Step 4: Reflect and debrief.

When students have finished the video, they will receive their individual score reports and SBAR score reports. The Individual Report provides an overall reasoning score, performance related to outcomes (QSEN, NCLEX Client Need Category, and Body Function), and feedback on questions answered. The question, selected option, and rationale for the option are provided.

Students will use the information from these reports to undergo a reflection of how they performed. The lesson plan provides specific assignments to help students think critically about the decisions they made and what they learned.

You can use these reports for debriefing but also as a remediation tool. For example, you can send students back into the scenario after they’ve reviewed their Individual Reports. Kane suggested that you ask students, “What did you learn? What did you pull away from this experience that leads you to make better decisions in the future?”