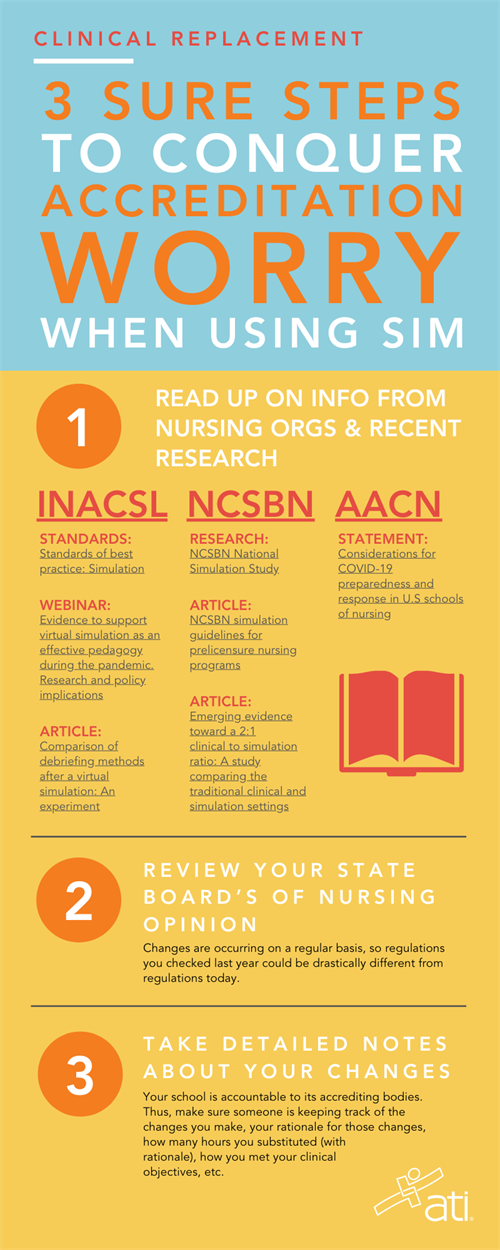

3 SURE STEPS TO CONQUER ACCREDITATION WORRY WHEN USING SIM

DOWNLOAD THE INFOGRAPHIC AS A HANDY REFERENCE

Follow the 3 steps here to put your program in a strong place when accreditors come calling.

Follow the 3 steps here to put your program in a strong place when accreditors come calling.1) GET FAMILIAR WITH INFORMATION FROM NURSING ORGANIZATIONS AND RECENT RESEARCH.

Nursing organizations published statements and opinions about the use of simulation as a substitution for clinical long before the COVID-19 crisis began. Since the pandemic started, however, many have updated those statements. Here are some facts for reference when backing up your teaching stance.• AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF COLLEGES OF NURSING (AACN)

Before the pandemic, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) stated simply, “AACN does not prohibit the use of simulation in offering quality clinical learning experiences.”Then, in November 2019, before pandemic concerns were widespread, AACN put a more positive spin on its perspective. Nancy Fahrenwald, PhD, RN, PHNA-BC, FAAN, Dean and Professor at Texas A&M University College of Nursing and Chair of AACN’s Government Affairs Committee, presented testimony before the House Committee on Small Business regarding the role of innovation in academic nursing. Dr. Fahrenwald educated the committee on the importance of clinical simulation in describing how her nursing school was using it to augment its nursing curriculum and “better prepare tomorrow’s practitioners and caregivers,” she said.

More recently, a March 20, 2020, statement prepared on behalf of AACN by Tener Goodwin Veenema, PhD, MPH, MS, RN, FAAN, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore), (“Considerations for COVID-19 preparedness and response in U.S schools of nursing”), stated:

“Schools of nursing are encouraged to develop contingency plans should future restrictions on clinical placements occur. These plans may include the expanded use of simulation, telehealth, and virtual reality in keeping with best practices and guidelines from state boards of nursing and other regulatory bodies; the use of online resources for teaching clinical care; and online group chat features.”

• NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR STATE BOARDS OF NURSING (NCSBN)

NCSBN is widely recognized for initiating the research on which institutions today rely regarding the use of simulation as a substitute for traditional clinical experience. Results of NCSBN’s study, published in 2014, “provided substantial evidence that up to 50% simulation can be effectively substituted for traditional clinical experience in all prelicensure core nursing courses under conditions comparable to those described in the study,” NCSBN stated.

Later, NCSBN strengthened that opinion when it convened a group of prominent experts to further support the information in the original study. That group published an article, “NCSBN simulation guidelines for prelicensure nursing programs,” in October 2015 in the Journal of Nursing Regulation. In that article, the group provided national simulation guidelines for prelicensure nursing programs. It based the guidelines on data from the original NCSBN study, previous research, a publication by the International Nursing Association for Clinical Simulation and Learning (INACSL) “Standards of best practice: Simulation,” and its own collective knowledge on the subject.

More recently, in May 2019, an article in Clinical Simulation in Nursing built on NCSBN’s original research. The article stated that a 2:1 clinical-to-simulation ratio was likely more appropriate than the 1:1 ratio that many state boards of nursing were using. Highlights of the article, “Emerging evidence toward a 2:1 clinical to simulation ratio: A study comparing the traditional clinical and simulation settings,” showed:

- Students completed more activities in less time in simulation compared with the clinical setting.

- Students spent more time in Miller’s Pyramid’s “knows how” level (application) in simulation.

- Students spent more time in Miller’s “does” level (independent action) in simulation.

The article — written by renowned experts Nancy Sullivan, DNP, RN, Sandra M. Swoboda, RN, MS, Laura Lucas, DNP, APRN-CNS, RNC-OB, C-EFM, and Chakra Budhathoki, PhD, all with Johns Hopkins School of Nursing (Baltimore); Suzan Kardong-Edgren, PhD, RN, ANEF, CHSE, FSSH, FAAN, and Janice Sarasnick, PhD, MSN, RN, of Robert Morris University, School of Nursing and Health Sciences (Moon Township, Pa.); Tonya Rutherford-Hemming, EdD, RN, CHSE, University of North Carolina, School of Nursing (Charlotte, N.C.); and Tonya Breymier, PhD, RN, CNE, University of Dayton, School of Education and Health Sciences (Dayton, Ohio) — concluded:

“The intensity and efficiency of simulation was demonstrated through the completion of more activities in higher levels of Miller’s Pyramid in significantly less time than clinical providing emerging evidence toward a 2:1 clinical to simulation ratio.”

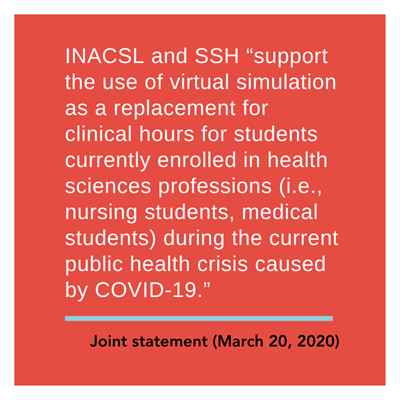

• INTERNATIONAL NURSING ASSOCIATION OF CLINICAL SIMULATION AND LEARNING (INACSL) AND SOCIETY FOR SIMULATION IN HEALTHCARE (SSH)

On March 30, 2020, INACSL and SSH issued a joint statement regarding the use of virtual simulation during the pandemic. It said the 2 organizations “support the use of virtual simulation as a replacement for clinical hours for students currently enrolled in health sciences professions (i.e., nursing students, medical students) during the current public health crisis caused by COVID-19.”

On March 30, 2020, INACSL and SSH issued a joint statement regarding the use of virtual simulation during the pandemic. It said the 2 organizations “support the use of virtual simulation as a replacement for clinical hours for students currently enrolled in health sciences professions (i.e., nursing students, medical students) during the current public health crisis caused by COVID-19.”

Signed by the two organizations’ presidents — INACSL President Cynthia Foronda, PhD, RN, CNE, CHSE, ANEF, Associate Professor of Clinical, University of Miami School of Nursing and Health Studies, and SSH President Bob Armstrong, MS, Eastern Virginia Medical School Sentara Center for Simulation and Immersive Learning (Norfolk, Va.) — the statement further said, “We can attest that virtual simulation has been used for over a decade successfully. Further, research has repeatedly demonstrated that use of virtual simulation — simulated healthcare experiences on one’s computer — is an effective teaching method that results in improved student learning outcomes.

“Based on the current and anticipated shortage of healthcare workers, we propose that regulatory bodies and policymakers demonstrate flexibility by allowing the replacement of clinical hours usually completed in a healthcare setting with that of virtually simulated experiences during the pandemic. By supporting this innovative yet effective way of teaching as a solution to address the clinical hour shortage of health professions students, education efforts will continue seamlessly, and we will support timely career progression of healthcare providers needed immediately to battle COVID-19.”

Since then, in a webinar presented on March 25, 2020, “Evidence to support virtual simulation as an effective pedagogy during the pandemic. Research and policy implications,” Dr. Foronda said, “When we look through the literature, we already have evidence that virtual simulation has demonstrated improved knowledge compared to other methods; decreased time to skill achievement; increased retention of material over time; and that students like it. They think it’s fun, and they’re satisfied by virtual simulation.”

She then mentioned an article she helped write that was published in the Journal of Simulation in Healthcare in February 2020. The article, she said, offered “evidence to support virtual simulation in nursing education.”

“In this systematic review,” she explained, “my team and I reviewed articles from 1996 to 2018. We applied PRISMA Guidelines; appraised and ranked articles using Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt’s Levels of Evidence; and we asked the guiding question: How does virtual simulation impact learning outcomes?”

The team’s rigorous search strategy ended up including 80 studies.

“What we found,” she said, “was that the majority of the evidence (n=69 studies, 86%) suggested that virtual simulation resulted in improved student learning outcomes. When honing in on the RCTs (randomized controlled trials), the majority (n=12, 70%) of those studies demonstrated that virtual simulation led to drastically significant gains in learning outcomes when compared to traditional methods.

“In conclusion,” she added, “the preponderance of evidence suggests virtual simulation improves learning outcomes. This information is really important, as many of us are transitioning to virtual simulation and other online means.”

“In conclusion,” she added, “the preponderance of evidence suggests virtual simulation improves learning outcomes. This information is really important, as many of us are transitioning to virtual simulation and other online means.”

Dr. Foronda also shared information on another article — “Comparison of debriefing methods after a virtual simulation: An experiment” — published in Clinical Simulation in Nursing in 2018. The authors investigated how to effectively debrief virtual simulations, studying different types of debriefing: in-person, face-to-face, or virtual. The results showed each cohort had equivalent learning outcomes.

“This is important evidence,” Dr. Foronda pointed out, “because it showed that whether you debrief face to face or virtually, you can achieve the same amount of learning.

With all that information, then, she indicated she felt comfortable in supporting simulation as a substitution for clinical hours — but not the 1:1 substitution ratio that many boards of nursing limit.

Instead, she said, “We cautiously suggest allowing a 2:1 ratio for substitution of virtual simulation for clinical practicum during this pandemic.”

She added “We want to ask boards of nursing/policymakers for flexibility related to limitations of clinical hours completed in simulated settings.”

In addition to reviewing the latest information from INACSL, you should also — as a matter of regular practice — match your simulation plans to the organization’s "Standards of Best Practice: Simulation." Specifically, make sure you consider:

- Simulation design

- Outcomes & objectives

- Facilitation

- Debriefing

- Participant evaluation

- Professional integrity

- Simulation-enhanced interprofessional education (IPE)

- Simulation operations (sim-ops).

(Access a copy of the INACSL "Standards of best practice: Simulation"SM for more details.)

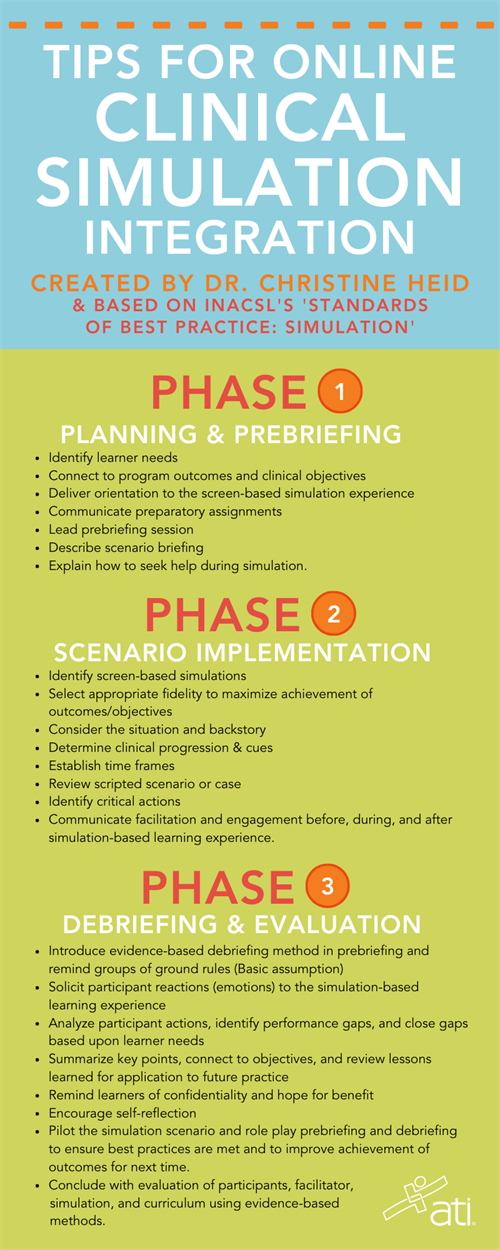

To simplify the use of INACSL's standards so you can most easily implement them into your simulation-based learning, Christine Heid, PHD, RN, CNE, CHSE, ATI Consulting Nurse Educator, has organized them into 3 phases.

(She explores and provides examples of each phase in action during a 3-part webinar series. You can access the webinars after you log in to the ATI website and click on "ATI Academy" in the far-left column. Then click "Content Library," search for and click on "Online Clinical Plans," and then scroll down to the 3 webinars that include "Phase" in their names. The webinar series describes role playing of how to conduct a prebriefing for screen-based simulation, how to review progress of virtual simulations, and how to conduct a synchronous online debrief.)

Below are INACSL’s recommendations for best practices, along with Dr. Heid's tips to consider when incorporating the best practices using her 3-phase plan for the simulation experience:

| INACSL'S "STANDARDS OF BEST PRACTICE: SIMULATION" SIMULATION DESIGN | TIPS FOR ONLINE CLINICAL SIMULATION INTEGRATION |

| PHASE I: PLANNING AND PREBRIEFING | |

|

|

| PHASE II: SCENARIO IMPLEMENTATION | |

|

|

| PHASE III: DEBRIEFING AND EVALUATION | |

|

|

(Refer back to INACSL’s Standards for more detail on each criterion.)

DOWNLOAD THE INFOGRAPHIC AT RIGHT AS A HANDY REFERENCE

2) REVIEW YOUR STATE BOARD’S OF NURSING OPINION.

Dr. Foronda’s recommendation for a 2:1 ratio may be having an immediate impact on some boards of nursing, as changes to their limitations continue to evolve. But, right now, you won’t find any uniformity among them.In a webinar presented on March 24, 2020, Carol Fowler Durham, EdD, RN, ANEF, FAAN, FSSH, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and K.T. Waxman, DNP, MBA, RN, CENP, CHSE, FSSH, FAONL, FAAN, California Simulation Alliance, offered tips on “Aligning simulation with COVID-19 contingency plans.” They first noted the lack of consistency among individual state boards regarding the number of required clinical hours per program.

“They are all over the map,” Dr. Waxman said. “There’s no consistency in the number of required clinical hours per program,” she added, pointing out that 25% of 1,000 hours is not the same as 25% of 600 hours — a reference to the percentage of clinical hours that can be substituted with simulation.

Like the comments made by INACSL’s Dr. Foronda, Drs. Durham and Waxman explained that — previously — many states had set a 1:1 ratio of clinical hours to simulation, despite studies showing the greater richness of simulation compared to clinical. In addition, they pointed out how much the percentage of accepted simulation substitution for clinical hours has varied, from 25% to 50%. During their webinar, however, new information was coming in as states began announcing loosened restrictions on their percentages in reaction to the pandemic. Some states, in fact, were allowing temporary waivers up to, apparently, 100%, such as Florida, Maryland, Michigan, North Carolina, and Wisconsin.

(Due to the constant changes currently taking place, make sure you verify your state’s regulations by visiting INACSL’s Simulation Regulation Map. Click through to your state for the most up-to-date information. You can also refer to NCSBN’s regularly updated document, “Changes in education requirements for nursing programs during COVID-19,” to learn what’s happening in your state.)

In an encouraging note, Dr. Waxman added that, once the pandemic is over, boards of nursing won’t simply resume their previous regulations.

“Our hope is, once we can show that we can make a difference and our outcomes are unchanged,” she said, “that we won’t go back to where we were. We will stay where we have been having success.”

3) TAKE DETAILED NOTES ABOUT YOUR CHANGES.

Accreditation visits have not stopped in relation to the pandemic. Instead, they have switched from the previous in-person meetings to virtual/online events. That variance doesn’t impact your need to show appropriate documentation for the changes you’ve made, however.Dr. Waxman noted in her webinar, “After the dust settles, schools will be accountable to the accrediting agencies about what they did, what was the rationale for what they did, and also discuss how many hours they substituted and what was the rationale for that. So, make sure there’s someone that’s really documenting carefully all those components.”

Similarly, Ann Smith, PhD, MSN, RN, FNP, CNE, ATI Education Specialist, advised attendees during a recent webinar organized by ATI, “Online Clinical Plans: Integrating ATI’s screen-based solutions for clinical replacement.” (This webinar is available on-demand for ATI clients in ATI Academy.)

Similarly, Ann Smith, PhD, MSN, RN, FNP, CNE, ATI Education Specialist, advised attendees during a recent webinar organized by ATI, “Online Clinical Plans: Integrating ATI’s screen-based solutions for clinical replacement.” (This webinar is available on-demand for ATI clients in ATI Academy.)She said, “You still have to be able to answer the question about how did a particular screen-based simulation or learning activity meet your clinical objectives.”

Dr. Smith reiterated that faculty are ultimately responsible in making sure they are taking the proper steps.

“It's up to you to make sure that you're following your board of nursing's current requirements, whether they've waived some percentages, or whether they've given extra guidance,” she said. It's also up to educators, she noted, “to make sure you are following best practices.”

SOURCES & ADDITIONAL READING:

- Gu, Yaohua, Zou, Zhijie, Chen, Xiaoli (April 2017). The effects of vSIM for nursing as a teaching strategy on fundamentals of nursing education in undergraduates, 13(4), 194-197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2017.01.005

- Nicely, Stephanie; Farra, Sharon Fostering learning through interprofessional virtual reality simulation development, Nursing Education Perspectives September/October 2015 - Volume 36 - Issue 5 - p 335-336 doi: 10.5480/13-1240

- Farra, S., Miller, E., Timm, N., & Schafer, J. (2013). Improved Training for Disasters Using 3-D Virtual Reality Simulation. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 35(5), 655–671. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945912471735

- Foronda, et al., 2016; Liaw, et al, 2014; Sunnqvist, et al., 2016; Tilton, et al., 2015; Ulrich, et al., 2014; Verkuyl, at al, 2017.

- Foronda, C.L., Fernandez-Burgos, M., Nadeau, C., Kelley, C.N., & Henry, M.N. (2020, February). Virtual simulation in nursing education: A systematic review spanning 1996-2018. Simulation in Healthcare, 15(1), 46-54.

- Verkuyl, M., Atack, L., McCulloch, T., Liu, L., Betts, L., Lapum, J. L., Hughes, M., Mastrilli, P., & Romaniuk, D. (2018, June). Comparison of debriefing methods after a virtual simulation: An experiment. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 19, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2018.03.002.

- Gordon, R. M. (2017). Debriefing virtual simulation using an online conferencing platform: Lessons learned. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 13(12), 668–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2017.08.003

- Padilha, J. M., Machado, P. P., Ribeiro, A. L., & Ramos, J. L. (2018). Clinical virtual simulation in nursing education. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 15, 13–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2017.09.005

- Rourke, S. (2020). How does virtual reality simulation compare to simulated practice in the acquisition of clinical psychomotor skills for pre-registration student nurses? A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 102, 103466. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0020748919302731

- Shin, H., Rim, D., Kim, H., Park, S., & Shon, S. (2019). Educational characteristics of virtual simulation in nursing: An integrative review. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 37, 18-28.

- Smith, S. J., Farra, S. L., Ulrich, D. L., Hodgson, E., Nicely, S., & Mickle, A. (2018). Effectiveness of two varying levels of virtual reality simulation. Nursing Education Perspectives (Wolters Kluwer Health), 39(6), E10–E15

- https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000369

- INACSL Simulation Regulations Committee. (March, 2020) INACSL Simulation regulation map. Retrieved from https://www.inacsl.org/simulation-regulations/